I couldn’t resist reading one more book on history that I noticed, when returning the previous batch to the local library: Niall Ferguson’s Civilization – The West and the Rest from 2011. It was interesting, because his angle is the same as mine, i.e. analysis of the factors that impact the relative competitiveness of various groups of people in different times. I am jotting these notes down today, before returning the book to the library, mainly for myself.

Ferguson chose “civilization” as the grouping of people for his study and analyzed it by testing his own hypothesis that the key factors that made the western civilization competitive were what he called the killer apps of 1) competition, 2) science, 3) ownership, 4) medicine, 5) consumer society, and 6) work ethics. The selection of “civilization” as the unit of competition was probably influenced by Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations from 1996.

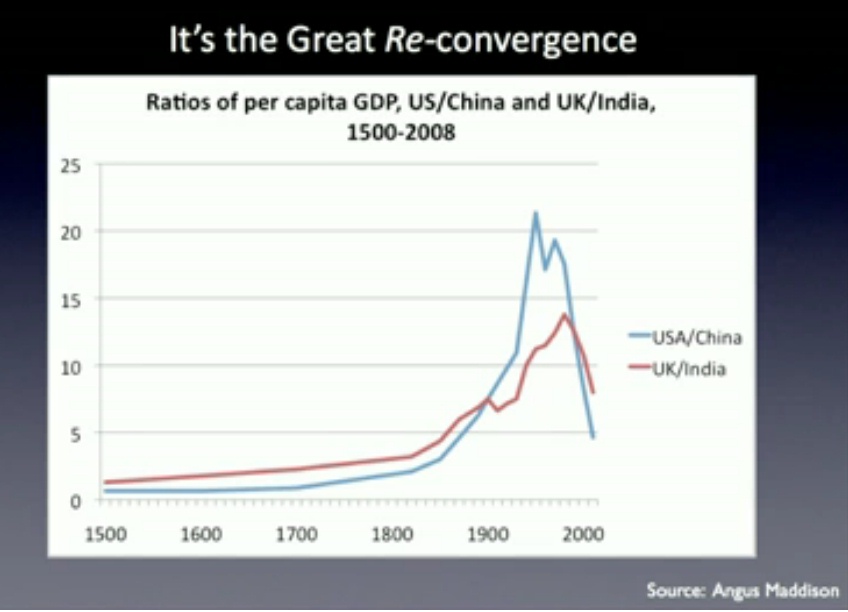

Ferguson’s argument is that these killer apps made the western civilization prevail over others during the last 500 years, but today we are seeing others “downloading the same apps” and we have yet to see how the new competition will play out. He addressed each killer app in its own chapter, probably aligned with the parts of the television series that was made as part of the book project, though I have not seen that television series.

In the chapter on competition, Ferguson starts by describing the difference between the mighty Chinese Ming dynasty in the 15th century and Europe in that same period. China was by far the richest empire in the world those days, its rice based agriculture 10 times more productive than Europe’s wheat based agriculture in terms of ability to feed a population. It had long traded with more western empires over the Silk Roads, but it also had the biggest ships, which were used by admiral Zheng He to visit India and Africa decades before Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route from Europe to India. But the Ming dynasty turned inward after Zheng He’s patron and emperor Yongle died in 1424. Building of large ships stopped and overseas exploration stopped for reasons that we do not know. The result was that China’s growth stopped as well and its economical equilibrium turned out to be fragile. By 1650, civil wars and diseases had cut the Chinese population by 35-40%.

Meanwhile, Europeans had survived the black death and continuous warfare between its small kingdoms, resulting in higher wages for the survivors and highly developed military technology based on continuously applied advances in science, which set them apart from the Ottomans and the Chinese. Europeans were looking for alternative trade routes to India in order to avoid paying duties to the Venetians merchants and the Ottomans (competition), who controlled access to the Silk Roads. The Spanish and Portuguese led the discoveries and established colonies.

The English and the Dutch followed suit, but armed with trading corporations under private ownership, which set them apart from the Spanish and Portuguese. In South America, the conquistadores were given large estates to rule in exchange for paying taxes, but the land was owned by the king. It was in the interest of the descendants of the conquistadores to keep the local population essentially as slave labor for the estates. In North America, on the contrary, immigrants were allocated plots of land to own and farm giving a foundation for entrepreneurship by the landowner class. Slaves were imported from Africa both to North and South America, as well as to Europe. That wouldn’t end until 19th century.

Ferguson’s argument about medicine centers on the period, when modern medicine nearly doubled the expected life of people in the west in the early 20th century and elsewhere in the second half of 20th century as it spread to the rest of the world. The industrial revolution was able to create economic growth thanks to citizen’s wanting and being able to buy its new mass produced products. Consumer society was needed and consumers became more valuable than slaves for the economies to grow. Finally, Ferguson compares work ethics to religiousness and argues that especially the protestant churches preached working hard as a form of worship in itself.

What is interesting is that today, especially China and other East Asian countries have adopted all of these “killer apps” and are challenging the west in the world economy, while some other parts of the world have been slower in their adoption, being left behind. Cultures evolve with interaction and interdependence. What interests me currently is not so much the competition between ancient civilizations, but rather the means of competition in the near future, when the internet has made ideas instantly accessible from anywhere in the world, when artificial intelligence makes it possible to automate most manual labor, when climates change, and when companies are global. My point of view here is distinctly European. We are being seen as a declining continent by much of the world, but things are pretty good here in many ways. My home country Finland is measurably one of the best places in the world to live in, as are several other European countries. So could we use some of these made-in-Europe strengths to regain our economic competitiveness in the future? Could there in fact be business opportunities for our existing or new companies? Should we change the interesting units of competing entities from civilizations to local areas or nation states or companies or something else?

—

Note: Title image (or its variant) was used by Ferguson in his book and the related TED talk. I found the graph via Google from here.